By Veena Narashiman ’2020

Originally a portmanteau of the words hack and marathon, a hackathon typically occurs over a day or two, bringing together computer programmers and others to solve a puzzle or invent a creative solution. During these 24- to 48-hour periods, participants are encouraged to form groups and collaborate, completing the hackathon with a rough prototype or ideas that can be presented to judges for prize money. Over the years, the adrenaline rush that often drives these competitions have created some famous “hacks”: the messaging app GroupMe and the Facebook “Like” button were both conceived during hackathons.

Although hackathons may feel new, they are nearing their twentieth anniversary. The concept was born in June 1999, when UC Berkeley alumni John Gage challenged attendees of a Sun Microsystems event to write a multi-user Internet program in Java for the Palm V. Almost two decades later, hackathons have been organized to advance all manner of technologies in practically every sector. And increasingly, hackathons have been launched to solve societal challenges, such as natural disaster preparedness and government transparency.

But are “hackathons for good” really effective, given that rapid prototyping is rarely a fix for entrenched societal problems? For technologists like Luca Ibota, a former Apple employee who has been active in many hackathons for good, the most important aspect is “identifying the problem you have and the ideal outcome you want.” In fact, said Ibota, the key to a successful hackathon for good is “precisely defining a problem or challenge.”

Still, some Cal students are skeptical about hackathons for good. The most cynical argue that incorporating buzz words such as “social impact” and “corporate social responsibility” at hackathons is a smart public relations move for technology companies looking to improve their public standing. Other Cal students insist that incorporating social good goals in hackathons is a testament to Silicon Valley’s aim to think more holistically and ethically about technology’s effects.

For many, UC Berkeley hackathons that take on a social impact lens are seen as a reflecting a student culture that prioritizes hands-on learning and that seeks to solve grand challenges like climate change and food insecurity. For Swetha Prabhakaran, a UC Berkeley sophomore and computer science student, the 21st century requires companies, nonprofits, and individuals to make solutions to intractable problems a priority.

Either way, the number of UC Berkeley hackathons focused on social impact is on the rise. Causes have ranged from building prosthetics for people with disabilities to developing apps that enable students to source fair trade goods. Student-run organizations have championed these hackathons as a way to ethically fill consumer gaps.

In April 2018, a partnership between the Sutardja Dai Center for Entrepreneurship and the UC Regents Chancellor’s Association hosted Cal Innovates, a hackathon aimed to bridge the engineering and business disciplines. Prabhakaran, who organized the event, said attendance was high because engineering and business students have started to “soul search” for meaningful impact. “Berkeley students have a strong entrepreneurial spirit—you can see it everyday,” said Prabhakaran. “But conversations about using business to help others are happening on small scale. The hackathon is a way to help students do this on a bigger scale.”

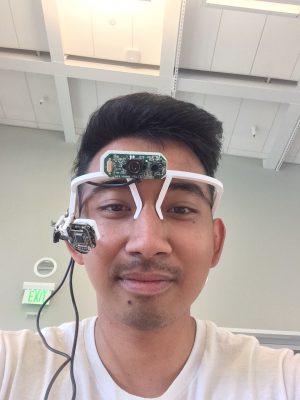

The Cal Innovates hackathon presented no strict problem to solve. It allowed participants—of which 40 to 50 percent were engineering majors and 30 to 40 percent were from the Haas School of Business—to build and plan deployment of prototypes. During the competition, participants listened to speakers or pursued their project with the help of guides. Professionals from SkyDeck, Cal’s startup accelerator, helped students with presentations and judged the finals, while employees of GoDaddy and students from BlockChain at Berkeley helped participants with technical aspects of their designs. Finalists included a project for civil engineers in developing countries to create sustainable bridges.

Another example of a UC Berkeley hackathon geared toward positive social impact was EnableTech’s “Make-A-Thon.” Held in April 2018, it aimed to connect those building prosthetics with those who use them, per the club’s motto: “Build with them, not for them.” Spanning 48 hours, the event allowed participants, formed into groups of six people from different majors, to rank which of EnableTech’s active projects should be improved. Kyelo Torres, a rising senior in mechanical engineering and the event project leader, spoke of the hackathon’s purpose: “As students, we are taught only theories. The second we are asked to do something, we get lost. The idea of hackathons is to practice the real world aspect of things.”

Amy Dinh, programs manager of the Jacobs Institute for Design Management, said she believes the reason for the uptick in hackathons with a social good emphasis is simple: “People seek a challenge, and there’s nothing more challenging than the wicked problems of the world.” Yet she dissuades students from expecting implementable solutions post-hackathon, highlighting instead the importance of the iterative process. “The point of a hackathon is to get creative juices to flow,” she said. “It’s not realistic for the ideas to be polished; rather the point is to kickstart a new team or idea.”