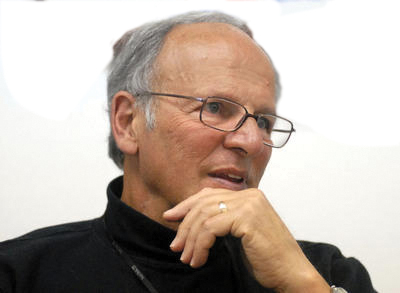

Dr. Bertram Lubin’s 50-year career is not coming to a close. Although the former president, CEO, and research director of Children’s Hospital Oakland—who has served as the principal investigator or co-investigator on over 30 National Institutes of Health grants, published more than 200 articles in peer reviewed journals, and co-authored the first clinical best practice guidelines for sickle cell anemia—is not, as he put it, “looking for an opportunity to advance my academic career,” he is also not interested in retirement.

This fall he joined the Blum Center and the College of Engineering to serve as a senior advisor in health, where he plans to mentor students and advise interdisciplinary faculty on health care-related research.

“I’m doing this because I enjoy it, because I see an opportunity to work with students and faculty to improve the health of children and their families, locally and globally,” said Lubin. “In my opinion, UC Berkeley is perhaps the best public research university in the world, has a strong a commitment to its community, and I want to encourage that with what I do.”

Lubin is in an unusually strong position to make a mentorship and advisement commitment, not just because of his professional successes, but because he has led a life of tremendous breadth. Born in New York City, he grew up in a small town outside of Pittsburgh, PA to parents who ran a fruit and vegetable store and did not attend high school. He became the first person in his family to graduate from college and then medical school, and went on to become the first Pediatrician to run a children’s hospital in California. He plays jazz drums, and once was asked to play a tune with Thelonious Monk. He is married to a Cal graduate, has several children of whom he is very proud, started the basic research program at Oakland Children’s Hospital called CHORI, and founded 40 years ago an NIH-funded summer research program that has provided basic and clinical research opportunities to over 1,000, mostly underrepresented, minority high school, college, and post-baccalaureate students who have used knowledge gained in the program to pursue STEM-related careers.

Lubin is widely known for advancing the concept of the social determinants of health and health equity, which can include such varied factors as early child development, food security, housing, social support, education, housing, and poverty. He concedes this concept, though now recognized as important, is not financially successful in the short term, but can improve the health of communities over generations and result in an enormous return on investment.

Lubin first built his reputation in pediatric hematology, particularly sickle cell disease. Beginning in the 1970s, he led a California program to introduce newborn screening for sickle cell disease, an inherited blood disorder that largely affects people of African descent and can lead to acute pain and chronic complications. When he began studying this disease over 50 percent of children with sickle cell were dying by age 5 from infectious disease complications as their immune system was compromised.

Lubin, who claims to have inherited a “resilience gene” (if there is one), was convinced that he could both reduce the suffering the disease causes and extend the life of patients. He and his colleagues thought that if sickle cell disease could be identified at birth, they could start antibiotics and prevent early mortality. The problem was how to convince the community of the value of newborn screening, especially African Americans, who had cause not to trust the U.S. medical establishment.

“I knew I had to do things that were widely accepted,” remembered Lubin. “I knew some members of the community might see the testing as earmarking them in a negative way, so I had to get them on board, which meant going to every possible community meeting.”

Community permission and funding came after a pilot project at Alta Bates Hospital in Oakland. The results were convincing: with a simple blood test, pediatricians knew if an infant carried the disease. They could then prescribe penicillin to prevent bacterial infection and affect lifespan.

“Everyone agreed that if the child had sickle cell, their life would be negatively affected and even at peril,” explained Lubin. “This then meant that everyone could accept identifying a child to prolong his or her life and institute prophylactic antibiotics. What we did in California was adopted across the United States. Now there isn’t a state that doesn’t screen for sickle cell anemia in the newborn period.”

Lubin went on to start the first sibling cord blood banking program in the world for children with hemoglobinopathies, which did lead to cures, and supported the application of gene therapy and bone marrow transplantation for children with sickle cell and related diseases.

Now 80, he looks back at these experiences with satisfaction and pride. He attributes much of his success to his passion to help others, particularly underserved children and their families. He believes the salesman ability he learned as a kid while working at his parents’ store played a major role in his life.

“[Medical research] funding often requires sales and communication skills,” he said. “As an NIH reviewer at a study section on a particular grant, I’d often have to convince the 30 other reviewers of the value of the proposed research. I do feel these skills are important if they are done in a way that the community respects and trusts.”

The sales boy turned doctor found these skills particularly useful when he was running Children’s Hospital Oakland. The staff selected him because they wanted a physician in the CEO position, who was committed to improving the health of all children.

“They knew that I brought with me the concept of the social value of children and the importance of improving the health of the overall community. It was what I believed in, and what our medical staff believed, was of value. It’s what a children’s hospital should be doing, especially one that serves 80 percent of children covered of Medi-Cal.”

Lubin plans to spend his time at UC Berkeley working with bioengineering faculty like Blum Center Chief Technologist Dan Fletcher on lifesaving medical devices with local and global application as well as emphasizing the importance of the social determinants of health—of seeing health care as holistic, interdisciplinary, and cross-sector. He also plans to help foster the university’s commitment to diversity and inclusion.

“I think we have to have health care leadership involved in public policy,” emphasized Lubin. “If you don’t get policy and implementation together, then you’re not going to move the needle. We need to stop pursuing small economic advantages. We need to focus on big impacts for society.”

Dr. Bertram Lubin is available to UC Berkeley students, research staff, and faculty for office hours and consultations. Please contact Yovana Gomez at yovgomez@berkeley.edu for an appointment.