Category: News

Berkeley to Host 2016 Clinton Global Initiative University

By Nicholas Bobadilla

From April 1st through 3rd, students, university representatives, policymakers, and topic experts from around the world will convene at Clinton Global Initiative University (CGI U), a three-day conference hosted by the Clinton Foundation that allows students to jumpstart and share innovative ideas for global change. Since 2007, CGI U has spurred thousands of change-makers to pledge their “Commitments to Action” in one of five focus areas: education, environment and climate change, peace and human rights, poverty alleviation, and public health. “Making a public commitment enhances personal accountability,” says Thato Keineetse, one of dozens of Cal students chosen to participate in the event. Former President Clinton and Chelsea Clinton will oversee the ninth edition of CGI U at UC Berkeley, which will host undergraduate and graduate students seeking to make the commitments that will usher their projects to completion.

The conference will include opportunities to exchange ideas, develop partnerships, network, and apply for funding to launch or expand projects. Universities in the CGI network must pledge at least $10,000 in support to participants, meaning over $750,000 will be made available for students to convert their ideas into action. Since 2008, CGI U participants, formally known as “commitment-makers,” have received $2 million in funding support and have made over 5,500 Commitments to Action. The conference will end with a Day of Action, in which students participate in a community-wide service event alongside local nonprofits or community organizations. This year, commitment-makers will work with Havenscourt Campus in East Oakland, a shared campus of four schools in the Oakland Unified School District that serves over 1500 students. Activities will include urban agriculture, mural painting, leveling books for the library, and cleaning the athletic facility.

CGI U participants undergo a competitive selection process. This year, Cal’s participants are engaged in projects ranging from 3D printing to microfinance to lobbying for LGBTIQ+ legislation. Find out more about them below.

Michelle Nie will employ the skills she has developed as a Business major to launch Māk, a social enterprise that empowers low-income youth by training them to design 3D printed products. Through an intensive, skill-building boot camp, the youth will learn to use 3D printing software. They will then work as interns for Māk, creating consumer products to be sold through the enterprise’s e-commerce website. Profits will be reinvested in future cohorts and more resources. Nie founded Māk alongside fellow business majors Ankita Joshi and Aubrey Larson, who started it as a project for a Social Entrepreneurship course. “I’m excited to learn about the amazing projects my Berkeley peers are working on and to connect and collaborate with students from around the globe,” said Nie.

MBA student Thato Keineetse’s Mo’H2O is committed to alleviating energy poverty and water scarcity in sub-Saharan Africa by making sustainable clean technology solutions more affordable. Mo’H20 will assemble, distribute, lease and service integrated solar water pump systems for low-income smallholder farmers in East and Southern Africa. Using an innovative business model, Mo’H2O will make it easier for people to pay for clean technology, while benefiting from increased productivity driven by a constant supply of water and access to cheap and reliable energy. “I’m excited to meet, share ideas, and work with others who have taken this step to transform their ideals into actions,” said Keineetse.

Big Ideas Finalist and MBA student Sneha Sheth seeks to give low-income mothers in India a leg up on their children’s development and educational readiness via an automated voice call service called Dost. The service provides a mobile platform that combats illiteracy by empowering mothers to deliver early learning experiences to their children. In giving mothers activities that fit into their daily routines, Dost represents a simple, innovative method of cultivating the potential of low-income Indian children. Sheth believes education to be the best way to alleviate poverty.

MBA student Zoe Beck will partner with UC Berkeley to produce and distribute a new MOOC on economic inequality. Former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich will teach the course, which will explore the ongoing economic inequality in the United States, its impacts on the nation’s economy and democracy, and what can be done about it. Intended to inform and engage, the course will feature filmed lectures as well as live interactive forums, and will emphasize steps students can take to make a difference.

Dedicated to alleviating poverty in the Bay Area through financial inclusion, Amanda Ng will work with a technology start-up called Insikt to find banks, insurance companies, retailers, and other businesses in Berkeley and Oakland that target low-income consumers whose credit histories make them ineligible for loans. Ng will lobby businesses to use Insikt’s lending platform, which employs an underwriting algorithm to assess the creditworthiness of potential borrowers, and determines a loan size and interest rate that maximizes repayment rates. Insikt’s efficiency in gauging financial potential, along with its current array of partners, make it a viable and accessible method of building capital among the poor.

Clintons, CGI University at Berkeley this weekend (UC Berkeley News)

Blum Faculty Isha Ray Publishes “Towards Gender Equality through Sanitation Access,” a Discussion Paper for UN Commission on the Status of Women

http://prod.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2016/3/towards-gender-equality-through-sanitation-access

Hombres Verdaderos: Training Youth to Confront Domestic Violence

Cal Bears in the Fight against Trafficking

By Sarah Bernardo

At a university with a long, illustrious history of social activism, it is easy for students to feel overwhelmed by the sheer number of movements and awareness campaigns being waged on the UC Berkeley campus. Certain issues seem to fall through the cracks. A dedicated group of Cal students is working hard to make sure that human trafficking does not become one of those overlooked issues.

According to Apurva Govande, the Co-President of the Anti-Trafficking Coalition at Berkeley, sex trafficking, child labor, forced labor, and bonded labor are not isolated issues, but “human issues” that touch every aspect of our daily lives from the clothes we wear to the food we eat.

While the anti-human trafficking community at Cal is small, interest in the issue has been growing rapidly. The Anti-Trafficking Coalition is taking a big step to grow awareness on trafficking and modern slavery by hosting their second “Freedom in Action” conference this Spring (on Sunday, February 28).

The conference is open to everyone, and this year’s theme is “Trafficking at the Intersections.” According to Kathy Brasil, the Coalition’s Publicity Chair, “we will be exploring many nuances of slavery and freedom through a keynote address from survivor and Cal alum Minh Dang as well as a number of unique workshops.” Dang is the founder of the Minh Dang Fellowship for Human Rights which focuses on the eradication of all forms of modern slavery. (The application for the fellowship is open to all UC Berkeley students, and one student is selected each year to serve as a Dang Fellow.)

Govande said, “As student abolitionists, we can often make a much greater difference than we realize. Just being aware of the issue can catalyze change for the people behind the issue: the men, women, and children that human trafficking directly affects.”

Dedicated anti-trafficking activists at Cal have been busy developing programs like the Human Trafficking Prevention Education DeCAL, which Govande says “does a great job of familiarizing students with the issue and brings in speakers each week that highlight different aspects of human trafficking.”

The Anti-Human Trafficking IdeaLab is another result of activist efforts. The IdeaLab is a multidisciplinary think tank that brings together students, academics, and community partners to tackle human trafficking. Their aim is to analyze the intersecting social issues that contribute to modern slavery and to present best practices for combating the issue at its source. No particular experience is necessary, so anyone with an interest in human trafficking is encouraged to join the IdeaLab.

This Spring at the Blum Center, world-renowned anti-trafficking activist and expert Siddharth Kara is teaching Global Poverty & Practice 140, “Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery.” (Read our interview with Kara here.) GPP 140 is an eight week course that examines various modes of exploitation within numerous contextual frames such as economics, culture, and history.

The renewed energy and attention on trafficking got a huge boost at Cal in 2013 when the Student Abolitionist Movement, the UC Berkeley chapter of the International Justice Mission, and Not For Sale combined to form the Anti-Trafficking Coalition at Berkeley. Brasil describes the coalition as a “student-run organization that focuses on educating students, raising awareness in the community, and advocating for more effective legislation in order to eliminate human trafficking in the Bay Area and beyond.”

Although the Human Trafficking Prevention DeCAL and GPP 140 are indications of increased awareness and interest, Russell Wilson, a former member of the Student Abolitionist Movement and advisor to the Coalition, says, “I would like to see more DeCALs as well as actual full credit classes taught on human trafficking. One thing that would be good is if a department such as the Social Welfare department would hire a person with both an academic and anti-trafficking background to create a curriculum around human trafficking.”

The “Trafficking at the Intersections” conference will feature a host of events to engage people who are new to the issues of human trafficking, as well as seasoned activists. Twenty different workshops will be offered, covering a range of topics including “Human Trafficking and the Superbowl Myth,” “Healing Through the Expressive Arts,” and “The Intersection of School-to-Prison Pipelines and Human Trafficking.” Legal professionals and academics such as Alameda County’s Deputy District Attorney Sabrina Farrell; Director of the Boalt School of Law Anti-Trafficking Project Alynia Phillips; and Federal Administrative Judge Marianna Warmee will be leading workshops. Representatives from non-governmental organizations, arts groups, and religious communities like CEO of Breaking the Chains Debra Woods and Reverends Amy Zucker Morgenstern and Debora Pembrook from the Unitarian Universalist Abolitionists will also host sessions.

In whatever way individuals choose to join the anti-trafficking community at Cal, they will be met with passionate and driven advocates. Govande, Wilson, and Brasil emphasize that the reason to become a part of this movement is that human trafficking is something that affects us all.

How Can You Get Involved?

Freedom in Action Conference 2016: Trafficking at the Intersections

Sunday, February 28 from 9:00 am to 4:00 pm

Grand Pauley Ballroom at UC Berkeley

The Anti-Trafficking Coalition at Berkeley meets every Monday 7:00 pm to 8:00 pm in 175 Barrows

Human Trafficking Prevention Decal

“Are These Kinds of Things Still Happening?” Siddharth Kara on Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery

By Sarah Bernardo

Siddharth Kara is a world-renowned expert on human trafficking and modern slavery. He lectures at both Harvard University and UC Berkeley, and advises the United Nations, the U.S. government, and many other governments, foundations, and NGOs on anti-trafficking policy and law. Kara is also the author of two books, the award-winning Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery and Bonded Labor: Tackling the System of Slavery in South Asia.

Siddharth Kara is a world-renowned expert on human trafficking and modern slavery. He lectures at both Harvard University and UC Berkeley, and advises the United Nations, the U.S. government, and many other governments, foundations, and NGOs on anti-trafficking policy and law. Kara is also the author of two books, the award-winning Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery and Bonded Labor: Tackling the System of Slavery in South Asia.

This semester, Kara is a lecturer at the Blum Center, teaching Global Poverty & Practice 140, “Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery.”

You first witnessed human trafficking the summer after your junior year in college while at a Bosnian refugee camp. You later went on to work as an investment banker and head your own consulting firm. What made you decide to return to the issue of human trafficking?

I had always been heavily impacted by that summer in the refugee camp, and at the time I was just too young to really process the experiences. So it was some years later when I was reflecting on the course of my life that I returned to the issue. I had worked in investment banking and learned quite a bit about the world of finance and economics. But I had always been affected and haunted by that summer. I was curious: are these kinds of things still happening, and if so is anyone doing anything about it? This was the late 90s, and I didn’t see much in the way of research. There were one or two narrative reports, but nothing analysis-based. So I thought, if I’m ever going to try something like this in my life, now is the time. I didn’t have formal training in human rights research, but I had a sense that this was an economic crime and that maybe I could make a contribution. I took my first research trip in the summer of 2000 across East Asia and Central Europe. The things I saw really overwhelmed me, and from that point I became dedicated to trying to understand and tackle the issue.

What is your opinion on the current state of human trafficking research and education?

The current state of human trafficking research and education is leaps and bounds ahead of where it was when I started my research almost 16 years ago. There are actually classes that you can take on the subject. There are books that have been written. Numerous research projects and reports are being conducted by researchers, NGOs, governments, foundations, and the UN. Having said that, there is still a tremendous research gap. The field suffered across the entire decade of 2000 to 2010 from not having sufficient focus on data gathering to understand the issue. For many years, there was a lack of credibility and legitimacy in anti-slavery work as a result of this deficiency. But that is changing now. There is more research being done, however there is still a significant data gap on human trafficking and slavery around the world.

When you are in acting in an advisory role for NGOs or governments, what is the most difficult aspect about addressing trafficking?

It’s very different depending on whether it’s a government or a non-government organization. With governments, much of my interaction has focused on a handful of challenges. One can be that they are generally in denial that their country has a significant issue or an issue at all with human trafficking. If they recognize that they have an issue, they want to frame it as an irregular migration problem and deal with it from a migration standpoint as opposed to a human rights and forced labor standpoint. They may not have enough data or information to guide their policy, or they may be reluctant to allocate the kind of resources that are required to address the issue both from a law enforcement standpoint and also from a victim empowerment and protection standpoint.

With NGOs, they have the passion and the courage to tackle the issue, but they may suffer from not knowing how to do research or how to measure the impact of their projects, which is very important from a donor standpoint. Data gathering and research is crucial to donors there days, and while NGOs are often in the best position to do this work, they may not necessarily be equipped or trained to do it.

There are also a handful of major obstacles to the successful punishment of human traffickers. One is there is a lack of systemic law enforcement focus on the issue. Two, there is a lack of understanding and training in how to identify traffickers. Three, there is a lack of protection and empowerment of victims who are crucial as witnesses to give information on traffickers and trafficking networks.

Do you think a capitalist economic system can ever coincide with the abolition of modern slavery?

I think so. I think market economy principles and economic globalization have to be recrafted into being a slightly more equitable system for all participants and non-participants, but that’s doable if world leaders want to achieve those goals. I think that will go a long way towards ridding the world of many of the push and pull factors that motivate trafficking and forced labor.

You are working on a film adaptation of your award-winning book Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery. What is your vision for the film?

I wrote the script for the film. I adapted many real world cases from those that I documented for my first book and from research that I’ve done since then to tell the first truly global and authentic feature film story on human trafficking. It tells the stories of three young women. One is from India, one is from Nigeria, and one is a foster care child in California. You follow their journeys of being trafficked around the world to the same place in Texas, along the way covering Europe and Latin America. The film spans the world because the issue is a global phenomenon, but the film is set here in the United States because the story of domestic human trafficking is remarkably under-discussed. You hear a lot of stories about trafficking in Cambodia, Nepal, India, Moldova, Nigeria, and Mexico, but not so much the United States. That’s starting to change, and I hope that this film sparks a conversation about the human trafficking problem right here in the U.S.

I hope the film will serve as a vehicle for generating new energy and resources to tackle human trafficking here and around the world. In support of these efforts, I will be doing several major events with the film with the UN and several governments around the world as well as NGOs to raise awareness and channel resources where they are needed. It will also have a theatrical release to touch the general audience. It has some fantastic stars in the cast, and I’m really looking forward to its release later this year.

How can average citizens contribute to the fight against modern slavery?

The first thing the average person can do is learn more about the issue by reading books and watching documentaries or films. The more you know the more effective you can be.

Two, spread that knowledge. Raise awareness among your peer groups, friends, co-workers, etc. That is a very tangible thing that people can do.

Three, support an NGO that works on this issue in some way. It could be financially or through volunteer work. It could be to help raise resources so that they can scale their efforts. Supporting anti-trafficking NGOs in some capacity is very important.

Four, engage with elected officials on the issue. Demand that they do more both from a sex and labor trafficking standpoint. In particular, on the labor trafficking side, one of the main areas of focus in the field now is how human trafficking, slavery, and child labor taint global supply chains of the things we purchase every day. I think people can get engaged in demanding that lawmakers set regulations for companies to ensure that their supply chains are untainted.

My report “Tainted Carpets: Slavery and Child Labor in India’s Hand-Made Carpet Sector” was the first major commodity-based investigation of slavery and child labor in the production phase of a commodity. It showed a model of how to do that kind of research and how to trace the products from the point of production to the point of retail sale. It showed you can get a sufficient sample size in cases documented to express prevalence rates of slavery and child labor in the supply chain. It made recommendations about how to clean up the supply chain. Ideally, one would do a series of commodity-based investigations and reports like that. I have a long list that I would like to do such as seafood, conflict minerals, garments, tea, coffee, cocoa, rice, and palm oil.

Five, use all the tools we have today like social media and communication to keep energy and momentum going so that you don’t have people getting excited and working on an issue for a while and then fading into something else. It’s important to use tools to keep people engaged, energized, and motivated.

Blum Center Receives First Higher Education Grant from Autodesk Foundation

Blum Center News

February 1, 2016—As part of its investment focus on supporting people and organizations using design for impact, the Autodesk Foundation has awarded UC Berkeley’s Blum Center for Developing Economies one of the Foundation’s first university grants.

February 1, 2016—As part of its investment focus on supporting people and organizations using design for impact, the Autodesk Foundation has awarded UC Berkeley’s Blum Center for Developing Economies one of the Foundation’s first university grants.

The Blum Center is among four higher education institutions—including the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology (Bangalore, India), Olin College (Needham, Mass.), and the Art Center College of Design (Pasadena, Calif.)—to be recognized for their impact design ecosystem.

Impact design is rooted in the core belief that design can be used to create positive social, environmental, and economic change, and focuses on actively measuring impact to inform and direct the design process.

“The Autodesk Foundation looked at hundreds of colleges and universities around the world engaged in impact design,” said Lynelle Cameron, president and CEO of the Autodesk Foundation. “We chose these four institutions for the strength of their programs and the diversity of their approaches. The Blum Center appealed to us because of its emphasis on human-centered design and experiential learning. We appreciate that the Blum Center’s impact design process relies on interdisciplinary collaboration for achieving breakthrough ideas and inventions.”

The gift will facilitate new courses and student initiatives that promote and support impact design. In particular, the Blum Center will launch a “Hardware for Good” challenge in its highly regarded student innovation competition, Big Ideas@Berkeley. Since its founding in 2006, Big Ideas@ Berkeley has inspired innovative and high-impact student-led projects aimed at solving problems that matter to this generation. The contest has sourced hundreds of innovations, and supported thousands of problem-solvers who have gone on to launch nonprofits, for-profits, and cross-sector partnerships that are scaling solutions across the globe.

In addition, the Blum Center will initiate a new project-learning track for students in the Development Engineering program. Development Engineering is an emerging field preparing the next generation of development practitioners totake an integrated approach to develop sustainable solutions. Utilizing human-centered design approaches, engineering expertise, and an economic framework, this emerging field combines cross-cultural learning, novel financing mechanisms, prototyping and scaling, rigorous evaluation, and new models for productive international collaboration.

“We are thrilled to be partnering with the Autodesk Foundation to support students and faculty who want to make a difference,” said Maryanne McCormick, executive director of the Blum Center. “Today’s greatest challenges require the expertise and collaboration of every possible field. A key ingredient of success is impact design, enabling more innovative, scalable, and measurable solutions.”

The Autodesk Foundation is the philanthropic arm of Autodesk, a multinational corporation that makes software for the architecture, engineering, construction, manufacturing, media, and entertainment industries. The Blum Center enables interdisciplinary problem-solving aimed at poverty alleviation and social impact, operating on the notion that a world-class, public university must be a force for addressing urgent and important issues. Since its founding in 2006, the Blum Center’s mission has been to train people, support ideas, and enable solutions.

“If we want more people using the power of design to address today’s epic challenges, we need to equip future designers and engineers with the skills, knowledge, and tools to do so,” said Joe Speicher, executive director of the Autodesk Foundation. “We chose to support the Blum Center for Developing Economies because of their success as an interdisciplinary hub for social impact studies and action that prepares the next generation of change agents.”

New Blum Center Courses, Spring 2016

This Spring, 2016, the Blum Center will be offering four new courses in the Global Poverty and Practice undergraduate minor, and the Development Engineering graduate minor.

DEVENG 290, The Syrian Refugee Crisis

Instructor: Kate Jastram

Course meets Mon-Wed, 3-4:30, Blum Hall 330

This course will examine the challenges facing Syrian refugees from a multidisciplinary perspective, asking questions about international law, State responsibility, the role of development and information technology, and the impact of gender and age on the protection needs of the refugees. We will use a mixture of lecture/discussion and in-class exercises to explore these themes, as well as others suggested by student interest.

GPP 140, Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery

Instructor: Siddharth Kara

Course meets Thurs, 2-5pm

This course will examine the various typologies of slave-like labor exploitation that persist in the world today – human trafficking, bonded labor, forced labor, the worst forms of child labor, and others. Each of these modes of severe labor exploitation will be analyzed, as well as the legal, policy, and civil society responses to the offences. The myriad forces that promote human trafficking will be investigated, including similarities and differences from one region, industry, or typology to another. The course will pay particular focus on the economic, cultural, historic, religious, and gender-based facets of modern slavery.

GPP 150, Engineering Social Justice

Instructor: Khalid Kadir

Course meets Mon, 2-5pm, Blum Hall B100A/B

Technology is often presented as the solution to social justice problems, including poverty, hunger, climate change, etc. In such narratives, technology is presented as a way to achieve social justice while avoiding struggles over power, distribution of resources, and historical accountability. In this seminar, we will attempt to unpack this narrative by exploring the complex relationship between engineering, technology, and poverty. Rather than focusing on narrowly construed quantitative measures of the impact of specific technologies upon poverty, we will attempt to understand the relationship between poverty experts – specifically, those who are focused on applying technology to solve issues related to poverty and social justice – and the objects of their interventions – impoverished, under-served, and socially marginalized individuals and communities.

Development Engineering: Reflections from a Development Impact Lab Postdoctoral Fellow

http://dil.berkeley.edu/development-engineering-reflections-from-a-development-impact-lab-postdoctoral-fellow/

Transforming Maternal Healthcare in Kenyan Slums

Five Questions for Development Engineer Rachel Gerver

Rachel Gerver is among the first generation of UC Berkeley students in Development Engineering, a growing field for graduate students focused on technological solutions for low-income regions. Gerver graduated from UC Berkeley in 2014 with a PhD in Bioengineering, where she investigated the application of Herr Lab technology for rapid point of care HIV monitoring and infant diagnosis in Kenya. She currently serves as a Biodesign Innovation Fellow at Stanford University, identifying unmet needs in medicine at hospitals and clinics and assessing the market size and competitive landscape for potential new medical devices. The Blum Center sat down with Gerver to learn more about her background and interests.

What were your career plans when you started your PhD and how did they change?

When I started the PhD in Bioengineering at UC Berkeley/UCSF, I thought I would pursue a career in academia and become a tenured professor. About halfway through the program, I realized that I was much more motivated by applied projects and helping to get new medical technologies to market, where they can have an impact on patients’ lives. I also became even more interested in how new technologies can help improve access to medical care for underserved populations.

What was the nature of your Development Impact Lab Explore Grant?

I received a DIL Explore grant to travel to Kenya and work with Family AIDS Care and Educational Services (FACES) to understand whether [Amy] Herr Lab technology could be applied to early infant HIV diagnosis. I spent time in the Nyanza province of Kenya, including Mbita, Kisumu, and Mfangano Island. I learned the importance of understanding the overall system in assessing what technologies can have an impact, and in particular the challenges of supply chains and logistics in bringing medical care to underserved regions.

What is exciting about the medical technology field?

The rapid growth in the medical technology space and the potential of new fields, including mobile technologies, big data, and genomics, to improve human health and access to healthcare around the world.

Where do you see yourself in five years or 10 years?

Continuing to work on technologies that can enter the market and improve human health around the world.

Who are the scholars or practitioners you most admire?

I greatly admire organizations that have worked to get new technologies into the market to improve access to healthcare in underserved populations, including PATH and D-Rev. I also admire physicians such as Paul Farmer, who have devoted their careers to improving global health from the field and inspiring others to do the same.

The Somo Project: Learning Lessons in Kibera

The Blum Center and the Sustainable Development Goals

By Sybil Lewis

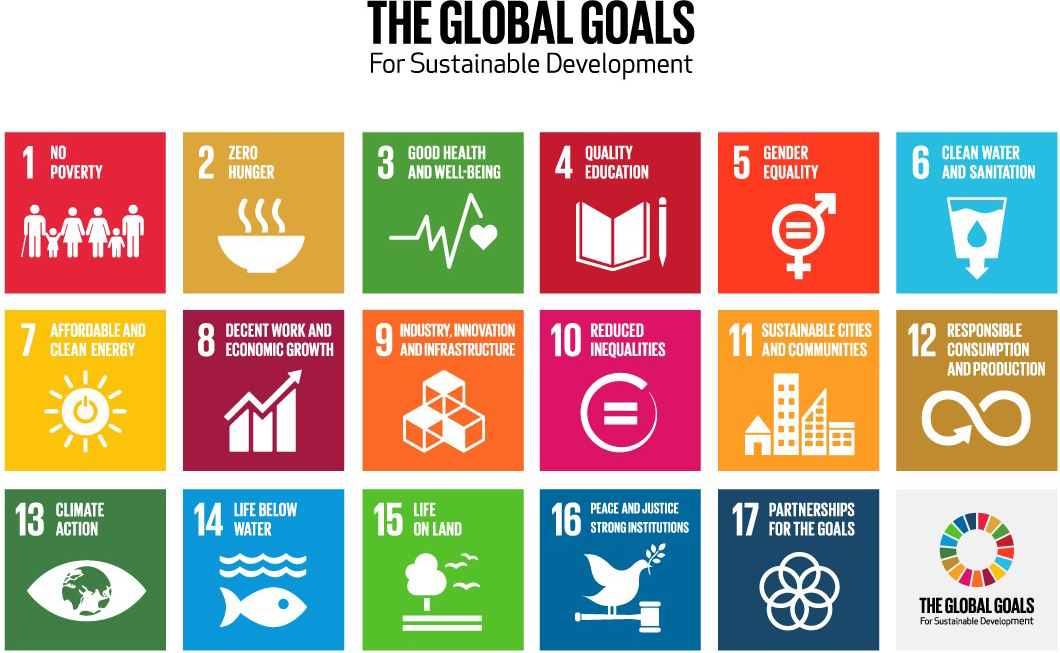

On September 25, 2015, the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, establishing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to end poverty, hunger, and inequality worldwide.

The robust set of goals was formulated and agreed to by 193 countries and represent, said UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, “an agenda for people to end poverty in all its forms—an agenda for the planet, our common home.” Also known as Global Goals, the SDGs comprise 17 goals and 169 targets, such as Clean Water and Sanitation, Gender Equality, and Climate Action.”

The Sustainable Development Goals replace the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which were established by world leaders in September 2010, along with a 15-year agenda to tackle similar issues including poverty, hunger, and child education. According to a 2015 UN report, the MDGs “produced the most successful anti-poverty movement in history,” reducing the number of people living in extreme poverty by more than half and achieving gender parity in primary schools in almost all countries.

While the MDGs were successful, progress has been uneven across regions and countries. Shortcomings remain in many target areas, such as climate C02 emissions that have increased by over 50 percent since 1990 and the fact that over 160 million children under age five have an inadequate height due to malnourishment.

The idea of the SDGs emerged at the 2012 Rio+20 meeting, where the dimensions of sustainable development were identified as environmental, social, and economic—thus broadening definitions of international development beyond economic indicators. Furthermore, the MDGs laid out eight goals for developing countries, while the SDGs acknowledge that sustainable development cannot be achieved unless all countries participate.

Since its founding in 2006, the Blum Center for Developing Economies has supported people and projects working to achieve several of the SDGs. Through the Development Impact Lab and the Big Ideas@Berkeley competition, the Blum Center has trained and promoted interdisciplinary innovations that deliver poverty-alleviating, sustainable solutions across the world.

Over the past 10 years, winners of the Big Ideas@Berkeley student innovation competition have developed numerous life saving and improving products and services—from portable power units providing electricity to medical facilities in Africa and the Caribbean, to a coalition of students and faculty working to reduce UC Berkeley’s greenhouse emissions.

The Development Impact Lab (DIL) is a global consortium of research institutes, nongovernmental organizations, and industry partners supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) that are committed to advancing international development through science and technology innovations. DIL is headquartered at UC Berkeley where students, faculty, researchers, and experts collaborate to create and implement various solutions.

For example, Darfur Stoves, a DIL and Big Ideas@Berkeley funded project, was started by a team of UC Berkeley researchers who designed a cookstove specifically for refugees of the Darfur conflict. Since then, the Darfur Stoves project has expanded, providing wind-resistant stoves to people in crisis situations in Ethiopia, Haiti, and Mongolia.

Click here to learn more about Blum Center teams advancing the Sustainable Development Goals.

An Interview with Lavanya Jawaharlal on Females of Color in STEM

By Carlo David

At age 22, Lavanya Jawaharlal is co-founder of a promising startup, a high-ranking officer within the UC Berkeley student government, and co-winner of a $200,000 award from the investment reality TV show “Shark Tank.”

Lavanya and her sister Melissa Jawaharlal, with whom she founded STEM Center USA in 2013, plan to use the award money for their nonprofit, which uses robotics and hands-on learning to teach Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math to diverse K-12 students.

Their win has produced high enthusiasm from the Berkeley community, but also a sense of relief for those, like Jawaharlal, who are eager to shatter the glass ceiling for American women in STEM. A 2014 University of California Hastings study found that 100 percent of women report gender bias in the STEM fields.

The Blum Center sat down with Jawaharlal to hear her views on the culture and politics of diversity in tech.

Did you ever imagine yourself appearing on national television to pitch your own business idea, let alone being the cofounder of startup that has so much potential for growth?

Not really. It all started in our living room, teaching robotics to the children of our family friends, who later brought their friends, whose friends brought more friends. We were basically doing what we were passionate about. But then our parents began to feel a little uncomfortable with the idea of having random kids in the living room. So we had to find a space, which eventually became STEM Center USA. Unlike other entrepreneurs, my sister and I never meant our project to grow into the organization it is today. But eventually we realized there is a need to do it.

What was your childhood like and how did it shape your passion for robotics?

My interest in robotics started when I was a kid. I was never really interested in playing with the toys my parents bought me. Instead, I was more interested in taking apart the toys’ gears. In addition to being an ethnic minority, I was someone you would describe as nerdy. I was known as Lavanya the Tomboy, someone whom everyone looked down upon. I did sports and I was into robotics. Coming to California from a small New Jersey suburb was comforting, because I realized I was not the only person of color with my interests. Once I got into high school, I became more interested in the mechanical aspects of engineering. My sister, Melissa, who is two years older than me, was also very passionate about hands-on learning. Together, we were able to combine our passions and introduce hands-on robotics learning to young students.

According to studies, women make up less than 25 percent of the STEM workforce. As a woman of color in STEM, how do you make sense of this gender gap?

It’s really frustrating. People tend to minimize the differences in opportunities available to men and women, but then you see the education and employment numbers and realize it’s not the case. The gender gap stems from societal issues. When girls are growing up, as soon as they enter elementary school, they are exposed to the notion that they should be good in arts, in drawing. In other words, they are taught to specialize in something that is socially agreed upon as gender appropriate. The same is true for the types of toys they play with; girls play with Barbies, while boys play with cars. At a young age, kids are taught to think and behave in a manner that is consistent with gender norms. This translates into gender-specific occupations. So while I find these statistics frustrating, I am not surprised by them.

Have there been instances, as a mechanical engineering student, as a young entrepreneur, where you felt intimidated or delegitimized?

I have never felt intimidated here at UC Berkeley, but there have been instances where I felt my voice was not heard. Because Mechanical Engineering is such a male-dominated space, I need to work twice as hard to make sure that my voice is heard. If I have an opinion on homework, I feel the need to get my opinion across. In labs, people unknowingly tend to ask questions more from my male colleagues, even if I have been in the lab for the same amount of time or longer. Also, I find that younger students tend to ask male students more questions. This bias stems from the fact that the struggles of women of color, especially those in STEM, are not discussed. When you work in spaces where the emphasis is more on technical aspects, the discourse becomes less about the gendered or racial nature of the environment.

What are some of the problems or deficiencies in the promotion of STEM to young students of color? What can we do better to ensure diversity in these fields?

One of the principles of STEM Center USA is the importance of hands-on learning. Today, in a lot of public school systems, the method of teaching and learning is very tedious: the teacher talks and the students listen and takes note. Essentially, this creates a system that is grounded more in memorization than the application of knowledge. We, at STEM Center USA, allow students to apply what they learn in math and science classes in hands-on opportunities like lab experiments. Also, we have seen significant budget cuts in math and sciences, which translates to gaps in learning. For students, the lack of resources and robust learning environments diminish their confidence and ability to take courses like algebra.

What advice would you give to young girls who aspire for a career in STEM?

If there’s an opportunity, take it. But the problem is the lack of opportunity for underrepresented students. So if you have the opportunity, take it and be proactive about it. One thing I teach our students is “You’re into robotics? Fantastic!” But it doesn’t mean that you have to be an engineer. It means you also consider being a teacher, an artist, an historian.

Where do you see yourself and your startup a year from now, five years from now? What do you wish to accomplish?

In the next year, we are aiming to open one or two more offices in Southern California. In five years, we are hoping to open 10 or 20 more offices around the country. And in 10 years, our goal is to operate internationally as well. A huge part of the job is replicating our model, while taking into account the logistics and legal side of setting up new creativity centers. If we are able to expand our operations in a lot of cities, we will allow many more STEM students to maximize their potential.

For further information on Stem Center USA, click here.

Gregory Chin’s Journey into Empathetic Medicine

By Nicholas Bobadilla

Gregory Chin grew frustrated with the PT Foundation halfway through his eight-week practice experience in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He was working with one of the foundation’s HIV/AIDs clinics, which provides confidential and anonymous STD testing and counseling services that once had been free.

A shift in the organization’s priorities from accessibility to sustainability resulted in a mandatory fee for all clients. To make matters worse, the clinic relocated, further restricting access to clients without reliable transportation.

Like any Global Poverty & Practice student at UC Berkeley, Chin had developed a radar for the kinds of problems he saw at the PT Foundation.

“I thought: You keep forgetting about the people you’re serving,” he said. “You keep running it to make sure this place survives, as opposed to making sure the community you’re working with survives.”

GPP students often recognize and then grow frustrated by the deficiencies of the organizations where they briefly volunteer. The theoretical aspect of the curriculum places heavy emphasis on the critique of poverty interventions. It’s this problematizing that the GPP minor is notorious for, constantly encouraging students to question their organizations and the roles they play within them.

While in Kuala Lumpur, Chin voiced his opinions and lobbied his coworkers for change, but he was aware of his limited authority as a foreign volunteer. He also understood that fixing the problems he encountered required a critical stance.

“We problematize everything we see and then feel frustration as a result. But the fact that we can be frustrated and accept that frustration is a way to motivate ourselves to enact change,” he said. “If we don’t think of why this is better or wrong or what harm it’s doing, we won’t be able to alter it.”

As a Cal student in his final year on the pre-med track, Chin intends to bring this critical mindset to his medical career. “I will incorporate GPP into my future profession by recognizing that there’s always something wrong and there’s always someone who’s not benefitting within a system,” he explained.

For Chin, the often single-pronged, scientific approach doctors take can ignore cultural factors that lead to disease. “It’s about contextualizing experiences, but also about understanding the roots of people’s experiences and using those to understand the systems that people come from.”

Eight weeks in Malaysia gave Chin the time to embrace this more empathetic and individualized approach to medicine—an approach he intends to take one step further. By seeing people as individuals, he hopes to better understand the complex connections they might share. This simple realization has allowed him to go beyond the frustration prompted by the GPP minor and envision a medical career grounded in the complexity of human experience.

“We focus a lot more on how different one person is from another or how different I am from somebody else, but we don’t always focus on trying to find connections,” he said. “When we find those connections, we’re reminded that an individual’s life is complex.”

I-School Course Teaches New Approaches to Measuring Impact

By Tamara Straus

Ever since Hansen Lui was a kid, he loved building things and then taking them apart. During his undergraduate years at UCLA, he said his most valuable experiences took place not in class but in translational research labs, where he got hands-on experience and applied biological knowledge. So when Lui matriculated into the UC Berkeley-UCSF Joint Medical Program (JMP) this summer, he went looking for a similar way to connect his hands and his mind with his medical studies.

At Cal’s School of Information, he found a listing for a course called Hacking Measurement taught by Dav Clark, a fellow at the Berkeley Institute for Data Science, and Javier Rosa, a computer science and development engineering graduate student. Hacking Measurement appealed to Lui because it promised an experiential learning approach to measuring people and the environment through mobile devices, remote sensing, and the Internet of Things—a phenomenon of increasing importance to the healthcare field.

“Typically, we healthcare professionals lack an understanding of what goes on inside a machine,” said Lui. “And if you don’t know how a medical device works, you can’t figure out how to make it better or—in the case of developing countries—more accessible, affordable, or usable.”

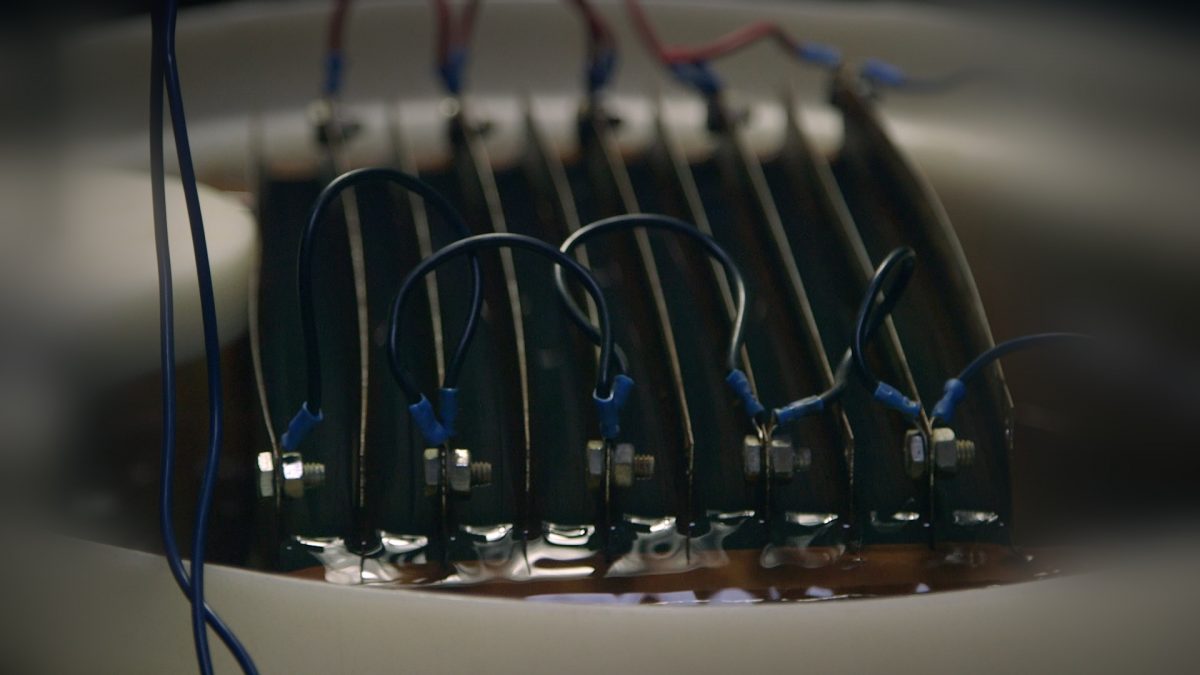

Lui, along with fellow Hacking Measurement classmates Joris Ramstein, another JMP student, and Jong-Kai Yang, a master’s student at the Berkeley School of Information, have been getting together nights and weekends during the fall of 2015 to create a prototype for a biosensing device called HeartBEAT. The technology is a portable, low-energy, bluetooth-enabled electrocardiogram that can record the electrical activity of the heart using electrodes placed on a patient’s body.

Although there are now several companies selling portable consumer EKGs, such as Qardio, Lui, Ramstein, and Yang aim to design their device for low-income patients and clinics. “If you look at the price of getting an EKG test at a U.S. hospital, it’s $30 to $100 every time with insurance coverage, and $300-$1,200 without insurance. We hope to make our device available under $100,” said Lui.

Yang noted, however, that the device is in early prototype stages and is not very user-friendly. He said he and his classmates are just as interested in tinkering with the growing number of sensors as they are in taking this one to market.

“It’s a very self-driven class,” said Ramstein. “We’ve been learning not just about how to collect and visualize data, but also about using geospatial satellite images to understand how environmental changes are occurring.”

Clark said he has been surprised that the biggest draw for the course has not necessarily been the seminars, which are conducted by himself, Rosa, and guest speakers such as Fabien Chraim, a Cal grad and CTO of the 3D geospatial intelligence provider Civic Maps, and Dawn Nafus, an anthropologist leading Intel’s Data Sense team. Rather, students are drawn more to the “CoLabs,” where the tutorials and practicums on subjects such as visualization and exploratory data analysis take place with support from the Social Science Matrix, the D-Lab, and Berkeley Research Computing.

All Hacking Measurement students are working with clients, who help determine a project’s road map. One such client is Peter Sand of ManyLabs, an open science network and maker space in San Francisco that is working with students on air quality sensors. Another client is Temina Madon, executive director of UC Berkeley’s Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA), which is working with students on text scraping and integration of economic development data. Yet another student team is working with UC Berkeley research seismologist Robert Nadeau on earthquake measurement and visualization.

Clark compares the measurement possibilities that come from sensors similar to the manufacturing possibilities that have risen due to 3D printers. “Once you understand that building and deploying sensors is something that’s possible and feasible, your idea about how to measure impact changes dramatically,” said Clark. “And with the ability to directly measure things come better results.”

Rosa, who devises technological interventions to alleviate poverty and inequality in low-income regions, is seeing that data measurement and analysis are rapidly changing the social sciences, specifically the field of international development.

Among the big changes Rosa has witnessed is in microgrid design. By deploying smart meters, he and his colleagues in the DIL-supported Rural Electric Power Project in India have been able to use sensors to figure out when people are using electricity, how much electricity they are using, and from there what is the appropriate microgrid size to ensure efficient rural electrification. Recently, Rosa has been working with Niuera to build FlexBoxes, which monitor freezer consumption to enable the integration of renewable energy into emerging regions.

“This is the way to figure whether and an intervention that costs, say, a quarter million dollars actually benefits users, whether it can scale, and in what contexts,” said Rosa. “Direct measurement has just become crucial to evaluating projects for their impact.”

Going “Beyond the Bowl” to Achieve Gender Equity in Sanitation

By Tamara Straus

In 2013 Isha Ray, a UC Berkeley professor and international water expert, received a request from UN Women—to determine whether progress on sanitation in the world’s poorest places has been gender equal.

“I realized I couldn’t answer that question,” said Ray, who has spent 16 years studying the intersection of economic development and safe water. “Having potties here and there doesn’t tell me whether they’re serving women’s needs. ”

Although access to sanitation in the world’s poorest places has improved markedly over the past decade and has become one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals announced by the United Nations in September 2015, the question of women’s needs, particularly menstrual hygiene management, has not been widely addressed in sanitation programs. This is largely because there are still many cultures that consider a menstruating female unclean, untouchable, or bad luck.

Among international development researchers, female-specific sanitation also has not received much attention. A forthcoming scholarly literature review by the UN’s Water Supply & Sanitation Council (WSSCC) has discovered that there has been very little analysis when it comes to the question of whether toilet access, design, or programs satisfy female needs around menstruation, menopause, and infant or elder care. And although there is a big push (and need) to implement off-grid toilets at the home level, there are few sanitation programs specifically designed to make sure low-income girls and women in developing countries have the access, privacy, and conditions they need to go about their public lives when they are menstruating, pregnant, or recovering from pregnancy.

“The WASH [water, sanitation, and hygiene] community is obsessed with stopping outdoor defecation and installing latrines at the household level,” said Archana Patkar, program manager of WSSCC, during a recent lecture at UC Berkeley’s Blum Center for Developing Economies. “This is important and necessary, but girls and women are not always at home—they are in school, they are working. And when they don’t have access to adequate sanitation and they are menstruating, 36 percent of girls and 96 percent of women don’t go to school or work.”

Facts like these have compelled Professor Ray, along with research partners Kara Nelson, a professor in UC Berkeley’s Department of Environmental and Civil Engineering, and Michael Lindenmayer, CEO of the nonprofit Toilet Hackers and a UC Berkeley visiting scholar, to commence an action-research project they are calling “Trisan: Going Beyond the Bowl to Achieve Gender Equity in Sanitation.”

The project, which has received seed money from the Blum Center’s Development Impact Lab, will research women’s needs for safety and privacy—not only for defecation, but also for urination and menstrual hygiene management. It aims to develop programs and practical education and outreach material in collaboration with WASH-related NGOs, girls’ schools in India, and the WCSCC.

Ray said during her past two years of research, she has found that most sanitation programs are still being designed implicitly for the male body’s needs. “Although the defection needs are the same, the urination needs are not the same,” she said. “Females cannot pee standing. They cannot use public urinals or go behind a tree. It’s not modest. So the ratio of toilet facilities to bodies in schools, slums, and streets needs to be examined.”

One of the arguments that Ray, Nelson, and Lindenmayer have begun to make is that sanitation programs should be geared explicitly toward female bodies and female needs. The reason, said Ray, “is if sanitation programs are designed for female needs, they will also serve male needs and disabled needs.” Men may not need to use a private latrine four times a day outside of their homes, but menstruating women do. This difference, argued Ray, should have a significant effect on current thinking around multi-family sanitation units in the world’s increasingly populous slums, settlements, and refugee camps.

So far, the Beyond the Bowl research team has not come up against much criticism with these initial research concerns, but it has gotten some important feedback. Among public health experts, said Ray, the questions they encounter are: What is your hypothesis? What are you going to test? Ray said those questions will be answered through their collaborative research. As for city planners, they point out that designing sanitation services for low-income women is more expensive. “Actually, I agree with that,” said Ray “But if it is, then it is, and we have to think about creative financing.”

Ray said she also agrees with those in environmental engineering who say that dealing with waste removal is imperative, and that flushable toilets in low-income public spaces in many developing countries are a long way off. “We must focus on these engineering questions, absolutely,” said Ray, “but we have to add menstrual waste to our waste disposal problems. We can’t just have fecal waste to worry about. Where are those pads going to go?”

Ray is quick to answer her own question: “Those pads are going into the toilet or into the pit latrine. Is it any wonder they fill up? Or they go in a girl’s bag, next to her books and her lunch. Or they are furtively tossed away. Or they have nowhere to go, so females stay home and miss school and work. All of these are bad solutions relative to creative financing.”

In the end, Ray and her colleagues believe the international community needs to start designing and promoting sanitation to achieve gender equality, in addition to public health. “One of the core principles of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations was the principle of nondiscrimination,” said Ray. “Human rights cannot discriminate by religion, gender, age, language, or sexual orientation. Yet I feel sanitation programs, with the best intentions in the world, in fact violate that core principle—because they’re geared toward defecation and not urination and menstrual hygiene management.”

The short-term timeline for Ray and her colleagues’ research is to build out their network of sanitation experts and sanitation-focused NGOs and to finish a position paper on achieving gender equality through sanitation, which they will present at the March 2016 meeting of the UN Commission of the Status of Women in New York.

“Of course, we’re not going to argue that we can achieve gender equality exclusively through sanitation; that’s crazy,” said Ray. “But we will ask the Commission to consider sanitation as a pathway towards gender equality—exactly as we would consider employment opportunities or educational opportunities pathways.”

Help Support the Blum Center During the Cal Big Give on November 19

Blum Center for Developing Economies will be participating in this year’s Cal Big Give, an annual one-day fundraising event to support students, faculty, and campus programs at UC Berkeley.

Some of our proudest accomplishments over the past decade have included:

- The Global Poverty & Practice minor, now the most popular minor on campus, has educated over 14,000 students in our classes, graduated over 600 alumni, and completed Practice Experiences in over 60 countries.

- The Big Ideas@Berkeley contest, in its tenth year, which continues to produce impactful innovations, and equally more important, encourages a diverse student population to think of themselves as innovators. To date, winners of the contest have leveraged at least $55 million in additional funding for their high impact projects.

- The Development Engineering minor for PhD students training them to improve human and economic development in complex, low-resource settings. Just launched last year, it is already being replicated in several global universities and training a diverse student body, including 50% women, with the 21st century skills they will need to make an impact.

To enable these and other great programs to grow and thrive, we hope you will consider supporting the Blum Center during this year’s Cal Big Give:

When: 9pm Wednesday November 18 – 9pm Thursday November 19 (PST)

What: Please visit the Blum Center giving page and select the “Blum Center for Developing Economies General Support” option to enable the our programs to grow and train even more students.

To support GPP or Big Ideas directly,

- Invite your family and friends to visit the GPP giving page and select the “Global Poverty & Practice Student Support” option to enable funding for practice experiences for current and future GPPers! Even a $10 donation will be greatly appreciated.

- Support the Big Ideas contest during the Big Give at the Big Ideas giving page. In honor of the Big Ideas Tenth Anniversary, we encourage you to give in the “Power of 10” (any multiple of $10 you feel comfortable giving).

What else: Please tweet a photo or a short story about your Blum Center experience and the hashtags #BlumGive, #BigIdeasGive, #GPPGive, and #CalBigGive (There are social media contests throughout the day, and we can win extra support from the campus, so Tweet as often as you like during those 24 hours)

Please contact sophi@berkeley.edu at the Blum Center with any questions!

Go Bears!!

Clarifying Poverty Action: A Profile of GPP Student Kristian Kim

By Nicholas Bobadilla

Kristian Kim decided to pursue a minor in Global Poverty & Practice because she felt a moral impetus to mitigate poverty. Instead, she found herself immersed in critical reflection and uncomfortable questions that forced her to examine her own role in the systems driving global inequality.

A double major in Development and Peace & Conflict Studies, Kim completed her practice during the summer of 2015 with AFSCME 3299, a labor union that represents University of California service and patient care workers statewide. She conducted research and interviews with workers, and examined how administrative decisions trickle down to affect their wages, job security, and benefits. Through her work, Kristian developed relationships with on-campus employees and gained a deeper appreciation for the people who make her life as a student possible.

“Getting to know people whose labor and struggle make it possible for me to come to school on a daily basis has tied me more to campus,” said Kim. “Understanding my relationship to them has helped me better understand my responsibility to support them as they struggle.”

That struggle involves a demand to be hired directly by the university, which currently outsources workers from private companies that do not provide the wages or benefits required to ensure economic stability.

Kim’s work on behalf of AFSCME 3299 also resonated with her personally. The socioeconomic struggle facing many campus workers, she said, resembled that of her own family members. Her grandparents fled North Korea in the 1950s and immigrated to the United States from South Korea with her parents in the early 1980s. Kim entered GPP knowing the sacrifice her family made to provide the stability in which she grew up. But witnessing the struggle of UC workers firsthand brought her closer to her own family’s hardships.

The Global Poverty & Practice minor is one of the most original, unorthodox, and progressive poverty studies programs in the country. (Full disclosure: I am a GPP minor.) Since its inception by the Blum Center in 2007, the minor has become one of the largest minors on campus, with students from numerous disciplines. GPP aims to supplement students’ chosen fields, encouraging them to engage with poverty on a systemic level and critically reflect on their own positions in relation to the problems they seek to address. In addition to teaching the prevailing theories on global poverty and development, the GPP program requires a minimum six-week “practice” component, in which students work with an organization dedicated to poverty alleviation or socioeconomic development.

Said Kim: “[GPP] gave me a different way of understanding some of the struggles my family members had as people, not just as stories, but as people who go to work and are exploited and struggle to make ends meet.”

Kim’s practice experience also reaffirmed the privilege she enjoys as a result of her family’s and UC workers’ sacrifices. This sense is not unusual among GPP students, who are taught to reflect on the factors that make their socioeconomic positions possible. It is an approach that ensures students are aware of the benefits they have, and it aims to prevent them from becoming complicit in the problems they try to ameliorate.

“My work with GPP contextualized my work with AFSCME and all my work in general. It’s given me a space to be critical without being paralyzed by cynicism,” said Kim.

Kim is referring to the commonly quoted words of Professor Ananya Roy, one of the founders of the minor who created its introductory course, GPP 115, at UC Berkeley. Roy often spoke of the “impossible space between the paralysis of cynicism and the hubris of benevolence.”

These words capture the essence of an educational program that provides an uncomfortable awareness of the factors responsible for systemic inequality. Students are encouraged to question their motivations and many come to recognize their own complicity in the systems that create global poverty. Kim is no exception, and expresses a deep awareness granted by the minor.

“GPP showed me things are messed up, but we engage with these forces every day. My choice to engage in specific aspects of struggles comes with the responsibility to fight those forces.”

This conviction drives Kim’s continued study of global poverty and her ongoing work with AFSCME.

“I move forward with that knowledge that I have a responsibility to undermine the systems that privilege me at others’ expense,” she said.

Such a realization has been possible due to the reflective tools provided by the minor. GPP 105 teaches students common methods used in fieldwork, while building habits for reflecting on the modes of power and inequality that come with their roles. It is this reflective component that Kim believes is one of the most standout features of GPP, in that it encourages students to go beyond the typical approaches to poverty utilized in academia.

“The way poverty alleviation is often approached at Berkeley is by looking at the global impact an organization can have, but that often comes with a disregard for the experiences of the people in poverty. This approach can undervalue the importance of these experiences,” she explained. “I think doing the work I did over the summer showed me I can’t ignore the way it [poverty] plays out in people’s lives.”

Kim recognizes the role she once played in perpetuating the conventions of poverty, yet the GPP framework has allowed her to step outside her previous mode of thinking and deconstruct those conventions.

“If you find yourself reducing people to things,” Kim said, “you need to face what keeps you from recognizing that your liberation is implicated in other people’s liberation. Thinking about poverty action that way makes it clear what you’re responsibilities are.”

blueEnergy’s Water and Sanitation Technology for Nicaragua

By Carlo David

The enormity of the world’s water and sanitation problems cannot be overstated. UN Water estimates that more than 3 million people die from water, sanitation, and hygiene-related causes each year, and nearly 10 percent of the global disease burden could be reduced through improved water supply, sanitation, hygiene, and water resource management.

In Nicaragua, the problem is no less dire. Among a population of just over 6 million, 48 percent don’t have access to adequate sanitation, according to a World Bank study—and 15 percent don’t have access to safe water, with much higher percentages for both needs in rural areas. This is particularly unfortunate because Nicaragua is known as the land of lakes and volcanoes; its rivers and reservoirs are far from parched like California. But it doesn’t have good water and sanitation infrastructure, which means many Nicaraguans rely on unfiltered water from groundwater sources, which are often contaminated by fecal matter.

That’s where NGOs like blueEnergy come in. Since 2004, the San Francisco-based nonprofit founded by Berkeley graduate Mathias Craig has been developing sustainable and community-based models to provide residents of Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast access to clean water and improved sanitation. Among its projects are biosand water filters, which use gravity and naturally occurring bacteria to largely eliminate water contaminants and provide safe drinking water. Since 2009, blueEnergy has installed 900 biosand filters, which have benefitted more than 4,500 residents.

While there are septic tanks and stand-alone latrines in the Nicaraguan towns where the nonproft works, such as Bluefields, these facilities are rare and expensive. blueEnergy navigates the lack of municipal-level water treatment facilities by working at the household level. With a team of research fellows, interns, and community members, the nonprofit is helping transform how residents access clean water.

“The biggest impact that blueEnergy has is we pull together all the dimensions of a solution—people, technology, financing, planning, management—in a setting where the challenges are complex and the service ecosystem is not very well developed,” said Craig, who graduated from Cal in 2001 with a BS in Environmental Engineering.

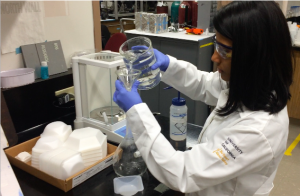

During the summer of 2015, Badisha Roy, a Berkeley undergraduate student in the Department of Chemical Engineering, interned with blueEnergy to conduct comprehensive testing on biosand filters distributed to Bluefields residents in 2010. Funded by Cal Energy Corps and the Berkeley Energy and Climate Institute (BECI), Roy is among an annual group of students chosen to participate in blueEnergy’s programs in Nicaragua.

Roy said implementing a project of this nature poses numerous structural challenges. Bluefields may be Nicaragua’s chief Caribbean port, but there is rampant poverty, high unemployment, and lack of economic growth. “Water and sanitation are so important and fundamental to people’s daily lives, but not everyone in Bluefields has access,” said Roy, who added that coming up with solutions requires “identifying people’s needs and how you are going to provide those needs.”

While blueEnergy maintains a small number of researchers and interns, it relies significantly on its local staff, community members, and senior fellows, who administer day-to-day operations and constantly train and educate beneficiaries about proper usage of filters and how to inspect latrines.

During her two month fellowship, Roy and her team examined hundreds of filters. After surveying 330 filters in 16 different neighborhoods, installed five years ago, they reported some positive outcomes.

“Generally speaking, most filters were functioning well. They met five or six of the eight parameters we have established to test the efficiency of these filters,” said Roy.

In extreme cases, while water sources and containers tested negative for E. Coli bacteria, the filtered water tested positive. These results demonstrated potential areas to be addressed to avoid reactivation of contaminants as well as the need for more conducting more community training on proper usage of the filters.

Although Bluefields has a long way to go in terms of economic development, filters introduced by blueEnergy have had some impact. Stay-at-home mothers reported being able to start small cafeterias and eateries in their own homes, without the fear of endangering their families and customers’ health by serving unfiltered water.

“Our goal for the future is to see the Caribbean Coast go from 80 percent being without clean water, sanitation, and electricity to 80 percent with clean water, sanitation, and electricity through direct service government partnerships and incubating new service-providers,” said Craig.

The Fast Trains of Mumbai: A GPP Grad Reflects on Living and Working in India’s Most Populous City

By Priyanka Athavale

Today was the epitome of the Mumbai fast train experience. It was utter frustration, suffocating stench, and packed with bodies. At the same time, the train felt systematic, organized, even solitary. This duality—a kind of chaos within order—is what defines Mumbai, the most populous city in India and the country’s financial, commercial, and entertainment capital.

For someone from suburban California, accustomed to organized roads and paved sidewalks, taking the trains is something of an adjustment. Yet I saw the transport as a feat—and not just any feat, a feat that thousands of Mumbaikars accomplished every working day. After four months in the city, my aim was to be a true Mumbaikar. Riding the fast trains would be the ultimate validation of my belonging.

I stood at the platform ready to board, my face sweaty, my palms clammy. The sun beamed in my eyes, as I read the digital sign blaring in red digits “F02,” indicating the fast train was approaching in two minutes. Mumbai’s trains are a miracle of mass society. Spread over a 465-kilometer network, they carry about 7 million passengers a day. Around 3,000 people die every year on the trains, most from falling or being pushed off the packed cars.

Standing there, I could hear my Indian family members warning me against the fast trains. I buried their sounds. I looked to my left, to my right, and felt a lump forming in my throat—the feeling you get when you’re about to drop 50 feet in a roller coaster. Seventy women stood at the platform, on par with me, ready to board the train.

Whatever confidence I had started to evaporate. I realized there was no way 70 people were going to board the train. It simply wasn’t possible. But there was no time to make an alternate plan. I needed to get to work. I had to board the train, and it was already in sight.

The train approached and then screeched to a halt. Women started pouring out of the ladies car. Pouring is an understatement. Women were flooding out. They were getting thrown out with their babies, their bags, their young children, all rushing to escape the havoc. There were women in saris, women in business clothes, women selling fish, women hocking earrings, fat women, thin women, old women, young women—they were like marbles gushing out of a bottleneck. At the same time, the 70 women on the platform were trying to get in.

Inside my head, I thought, “THIS IS RIDICULOUS!” but maintained a calm exterior. There were collisions, verbal conflicts, insults. Women were shoving other women, defending their bags, moving haphazardly—and all the while, I was getting sucked into the crowd with my two bulky bags. I closed my eyes and let the crowd take me in.

I appeared composed yet inside I was fuming: This experience should not be the norm for millions of women. The trains have to change—they needed a total revamp! The only thing calming me down was John Mayer blasting through my headphones, “Waitin’ on the world to change.”

Fury and fuming are familiar emotions in Mumbai. During my initial days, I questioned the streets crowded with rickshaws, the cows roaming aimlessly, the myriad of fruit and vegetable carts, the stray dogs and cats, and the street dwellers scattered on the sidelines. Everyday, I saw street children, some crying, some sleeping, some basking in the sun, and their mothers trying to manage a thousand things at once.

As Fulbright-Nehru scholar, my purpose in Mumbai was to conduct qualitative research on maternal barriers to child nutrition among families making less than $5 a day. I considered myself part public health researcher, part anthropologist, and part humanitarian. But when I walked through the streets of Dhobi Ghat, a large Mumbai slum, all I felt was appalled. My eyes stuck on corner stores selling junk food, the mildew-stricken jugs containing “fresh” water, and the half-clothed children wandering barefoot between homes.

Yet the mothers I encountered expressed hope about the future, despite the conditions they face. They are among the most inspiring and energetic women I will ever met—household managers, caregivers, and wives facing multiple daily lacks—of toilets, adequate food, clean water, effective education, and access to basic, affordable healthcare.

Mumbai is rife with juxtapositions: of affluence and poverty, of technological advancements on the one side and lack of electricity on the other, of towering highrises shadowing low tin-ceiling slums. How can a place like this be? The answer lies in the intrinsic necessity to survive. The city has an intangible energy; it is a place where resilience blossoms from struggle.

Back in the train, I let myself be taken through the crowd. Gradually, I realize I am part of team, a group of women, albeit complete strangers, who share a common cause and are helping each other toward it. The women guide me through the battleground of the train car and allow me to pass through. I find a little oasis near the window where I can stand.

I take a deep breath of air—the feeling of relief is unmatched to any I’d felt before. I look around and notice every woman is engaged in some activity: talking, sleeping, people watching, holding onto children, selling trinkets. I am just another woman in the crowd, trying to get to my ultimate destination. This train is a microcosm of the city. It could use some oiling, but it works and it has been working for years.

Priyanka Athavale graduated from UC Berkeley in 2014 with a double major in Molecular and Cell Biology and Public Health and a minor in Global Poverty & Practice. She was awarded a Fulbright-Nehru Fellowship to study barriers to improved nutrition and health practices in the urban slums of Mumbai, India.

Turning Feces to Fuel in Kenya

Undergraduate Research on the Rise at Cal

By Tamara Straus

Over the past year, UC Berkeley PhD student Zack Phillips and a team of six undergraduates assembled an LED array dome to fit on the Fletcher Lab’s CellScope microscope. The LED array did exactly what the team hoped for: it allowed the smartphone-enabled device to function as three separate microscopes.

Over the past year, UC Berkeley PhD student Zack Phillips and a team of six undergraduates assembled an LED array dome to fit on the Fletcher Lab’s CellScope microscope. The LED array did exactly what the team hoped for: it allowed the smartphone-enabled device to function as three separate microscopes.

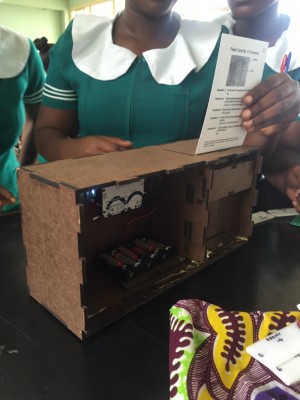

Phillips, who works with Assistant Professor Laura Waller in the Computational Imaging Lab, notes that the adapted device is still too fragile to be field tested for tropical diseases. But he is willing to admit that his team’s youthful composition and the speed of their invention are impressive. Phillip’s research group consists mostly of 19- and 20-year-olds and they completed their project in about 800 hours. The team’s next step is to take their $1,000 version—combining the imaging power of three $10,000 microscopes—and turn it into something sturdier that eventually can be priced for clinicians in developing countries at around $500 (not including the cost of the smartphone).

Professor Waller is certainly proud of this young team’s latest innovation. Yet she underscores that her research group and many others in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences have plenty of accessible projects for undergraduate students and that plenty of undergraduate students are making valuable research contributions.

In the case of the Cellscope project, supported by the Blum Center’s Development Impact Lab, it has offered undergraduates the chance to tinker with Arduinos—an open-source prototyping platform based on easy-to-use hardware and software—that are often taught in high school. Other reasons for increased undergraduate involvement and research contributions, says Waller, include: the “maker movement,” which has popularized lab invention, and the affordability of 3D printers, which allow research groups to iterate new versions in a matter of hours.

“It’s totally different now that when I was an undergraduate,” says Waller. “There were 3D printers then, but now we have access to them.”

Waller points out that college student research contributions are also due to a general attitude about the reciprocal nature of undergraduates in university research. Both sides have something to gain—professors gain engaged college students and students gain a useful learning experience.

“Research is a really nice way for undergraduates to understand the real-world application of their skills and operate in an environment that’s a little bit more like a real job,” says Waller. “It’s a fantastic supplement to their formal education that will serve them better in their future careers.”