By Tamara Straus

When Ryan Shelby left UC Berkeley with a PhD in Mechanical Engineering in 2013, he and his advisor considered his dissertation unusual. Shelby’s PhD research went beyond traditional engineering. It presented design theory and methodologies and was based on his involvement in building sustainable housing and renewable power systems with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation in Ukiah, California.

When Ryan Shelby left UC Berkeley with a PhD in Mechanical Engineering in 2013, he and his advisor considered his dissertation unusual. Shelby’s PhD research went beyond traditional engineering. It presented design theory and methodologies and was based on his involvement in building sustainable housing and renewable power systems with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation in Ukiah, California.

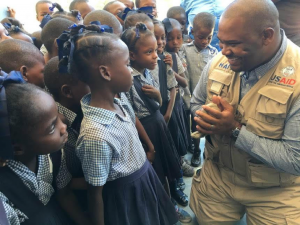

“Looking back, I was a bit of an odd duckling,” said Shelby, now a Diplomatic Attaché and Foreign Service Engineering Officer at the United States Agency for International Development in Haiti. “I wanted to do PhD work that was applied and more meaningful in a development context.”

Shelby failed his first qualifying exam. But the setback forced him to delve beyond engineering and become a technology for development polymath. He steeped himself in business, environmental science and policy, ethnographic studies, development theory, information technology, and the history of Native American tribes. When Ryan was handed his diploma, he continued along this interdisciplinary path. During the summer of 2013, he served as a Science, Technology & Innovation Fellow at the Millennium Challenge Corporation. He then worked in Sub-Saharan Africa and other emerging regions as a senior energy advisor for the U.S. Office of Energy and Infrastructure, landing in 2016 the position as a USAID foreign service engineering officer.

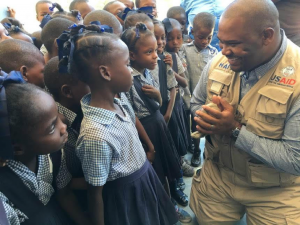

At USAID, Shelby has been developing and managing Haiti’s Build Back Safer II program, for which he recently won an award. Build Back Safer II provides local job training and material sourcing for hurricane-resistant building structures. To date, the program has resulted in 4,000 home roof repairs, the training of over 2,000 people (60 percent women) in roof rehabilitation techniques, and the completion of scores of handwashing and toilet facilities in areas damaged by Hurricane Matthew. Build Back Safer’s II next stage of repairs will focus on microgrid rehabilitation, water point upgrades, and sanitary block restoration in health clinics.

At UC Berkeley, Shelby remains a model for engineering Berkeley PhDs who want to do interdisciplinary research in low-income regions and use their technology skills. The graduate program in Development Engineering comes in part out of his quest to do applied engineering at the dissertation stage. To learn more about his trajectory as well as his views on engineering co-design, the Blum Center spoke with Ryan Shelby from his USAID office in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

How did your upbringing influence your academic and career pursuits?

I grew up in really rural Alabama, in Letohatchee, where there were about 600 to 700 people. My Dad had a farm there. I always liked to tinker—mess around with my Dad’s tractor, take apart my Mom’s vacuum cleaner. Luckily, my parents indulged me and I had a natural affinity for math. They let me to go to Alabama Agricultural & Mechanical University, an historically black college that had a very good engineering program. I majored in mechanical engineering with a focus on propulsion systems. It was 2003/2004 when President Bush talked about going after more alternative, sustainable energy approaches. That was pretty exciting to me, but Alabama A & M didn’t have an energy program. That’s when the dean of my university, Dr. Arthur J. Bond, told me about UC Berkeley and Professor Alice Agogino. He made the connection for some mentoring with her, and she encouraged me to apply. She said I could pursue design, energy, and engineering work.

Would you advise engineering PhD students to do applied work while in university?

In academia, there’s a lot of amazing ideas and technologies. But transferring those ideas into a practical technology that can be built and implemented at scale and have impact within a short time horizon—that’s not something easily done. Still, I would encourage people do this in an academic setting, because it’s a lot easier to do theoretical and applied work and fail and learn from those mistakes, as opposed to when you’re out in the policy world or in industry. The more you ideate, the more you fail, the more information you gather. It allows your next version to reach a more optimal solution.

How does USAID view university-incubated innovations?

The applied work university researchers do makes it a lot easier for us on the government side to say, “It’s been peer-reviewed and tested. Now let’s learn from what the Ivory Tower has done and integrate the work into our projects.” That’s how USAID under the Obama administration and now under the Trump administration is approaching university innovators. We realize universities have great ideas; they may be too high risk for industry to fund. But the U.S. government is willing to make informed decisions to invest in these technologies, so we can grow them and integrate them into our work—and ideally leapfrog pitfalls some countries face in their self-reliance and overall growth.

Are you working with universities in your Build Back Safer II program in Haiti?

Yes, we are partnering with the American University of the Caribbean in Les Cayes, Haiti and the Swiss Development Corporation to develop training programs on rehabilitation techniques and housing upgrades for homes and other vertical structures that were damaged by Hurricane Matthew. We identify masons and carpenters and others in the community who have some technical skills and interest in learning new vocational skills, and train them in hurricane repair and making proper foundations. We’ve combined that with vendors in the area, to source the right materials, so they can go out and implement a lot of these repairs—on roofs, water distribution points, and on two solar microgrids in the southern part of Haiti.

What combination of skills did you deploy to develop this program?

I designed this program because of my experience with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation. Coming in and putting in a solution that does not fit the cultural context is not the best way to ensure sustainability and self-reliance. Rather, you need to understand community needs, understand situated knowledge. In Haiti, we want to give community members access to the latest technology and building techniques. For me, this requires learning the Haitian way of building, and co-creating a shared knowledge base of how we can go out and do housing repair work that pulls from these knowledge bases. One the traditional building techniques here is called clissage, where you weave pieces of wood of varying tensions to create strong foundations and vertical structures. What we’re doing is showing Haitians how they can bolt onto clissage more modern and hurricane-resistant techniques for roof design and installations.

I designed this program because of my experience with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation. Coming in and putting in a solution that does not fit the cultural context is not the best way to ensure sustainability and self-reliance. Rather, you need to understand community needs, understand situated knowledge. In Haiti, we want to give community members access to the latest technology and building techniques. For me, this requires learning the Haitian way of building, and co-creating a shared knowledge base of how we can go out and do housing repair work that pulls from these knowledge bases. One the traditional building techniques here is called clissage, where you weave pieces of wood of varying tensions to create strong foundations and vertical structures. What we’re doing is showing Haitians how they can bolt onto clissage more modern and hurricane-resistant techniques for roof design and installations.

Is there a fairly straight line from your doctoral work to your current USAID work?

I told Alice [Agogino] it’s like déjà vu. My work in Haiti is almost a mirror image of the dissertation work I did at Berkeley. It’s still housing, design, and rehabilitation work, and it’s also energy systems to provide electricity to support economic growth. This is the exact thing I did with the Native American tribe. I’m using the same research techniques and codesign methodology with these Haitian communities. If I hadn’t done this dissertation work at Berkeley with Native American communities in California, I would find my job at USAID hard to do. I wouldn’t have the theoretical background or the tangible experience to prepare me for this work.

Which thinkers would you recommend to students in development engineering?

I highly recommend [UC Santa Cruz Professor] Donna Haraway’s work on situated knowledge as a core tenet of co-design and co-creation. Situated knowledge pulls from environmental science policy and feminist theory, and provides an intellectual framework for understanding and utilizing people’s knowledge bases. I also recommend [Harvard Professor] Sheila Jasanoff’s work on the co-production of knowledge and [Rutgers University] Frank Fischer’s work on citizens as experts of the environment. Dr. Fisher writes about how communities work with outsiders to understand environmental impacts and how to try to design and implement solutions.

How has the field of development changing, particularly for the U.S. government?

It really hasn’t changed that much between Administrations. Both the Obama and Trump Administrations have pushed to work with nontraditional actors, including universities. One big difference with development under the Trump Administration is we’ve increased the focus of self-reliance and co-creation. Our goal is to partner with a host country governments and co-design solutions with them, so that the host country itself can do the implementation work and not have to rely fully on the U.S. government. Under the Trump Administration, USAID is committed to streamlining our procurement approaches and increasing the usage of co-creation design approaches within new awards by 10 percentage points in Fiscal Year 2019. We want to continue to partner with universities, partner with private sector, partner with religious groups, partner with other nontraditional actors—so we can get the best technologies, solutions, and innovations to fit the needs of a host country government and get it out in the field as quickly as possible. The aim is to improve their resiliency and self-reliance and reduce their overall dependency on U.S. foreign aid as well as eventually open up new markets for American goods and services.

What would you recommend to Development Engineering students who want to work for USAID and other governmental organizations?

The transition from a more research background into development or the policy arena can be as perilous as crossing the sea with the sirens Scylla and Charybdis on either side. To navigate this path, I would recommend engaging in more applied research while at Berkeley with professors like Alice [Agogino], Alastair [Iles], Ashok [Gadgil], and Dan [Kammen] to get a better understanding of this space. Next, I highly recommend that students consider pursuing science and technology policy fellowship programs, such as the Christine Mirzayan Science & Technology Policy Graduate Fellowship Program at the National Academies, the California Council on Science and Technology, or the Institute for Defense Analyses Science and Technology Policy Institute (STPI) Fellowship. These programs are designed to help Bachelor, Master, and PhD candidates and recipients to understand how science is utilized in development and policy making. My experience as a Fall 2012 Mirzayan Fellow was instrumental in helping me land my job at the Millennium Challenge Corporation and USAID, as the National Academies taught me how to translate science and engineering speak into the language and format of a policy brief. Moreover, I was able to use my time at the National Academies to conduct informational interviews with development professionals within government as well as in for-profit and nonprofit organizations, to better learn which technology gaps and other seemly intractable problems that were encountering. These interviews and the knowledge that I gained were instrumental in helping me find and land a position at USAID.

When Ryan Shelby left UC Berkeley with a PhD in Mechanical Engineering in 2013, he and his advisor considered his

When Ryan Shelby left UC Berkeley with a PhD in Mechanical Engineering in 2013, he and his advisor considered his  I designed this program because of my experience with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation. Coming in and putting in a solution that does not fit the cultural context is not the best way to ensure sustainability and self-reliance. Rather, you need to understand community needs, understand situated knowledge. In Haiti, we want to give community members access to the latest technology and building techniques. For me, this requires learning the Haitian way of building, and co-creating a shared knowledge base of how we can go out and do housing repair work that pulls from these knowledge bases. One the traditional building techniques here is called clissage, where you weave pieces of wood of varying tensions to create strong foundations and vertical structures. What we’re doing is showing Haitians how they can bolt onto clissage more modern and hurricane-resistant techniques for roof design and installations.

I designed this program because of my experience with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation. Coming in and putting in a solution that does not fit the cultural context is not the best way to ensure sustainability and self-reliance. Rather, you need to understand community needs, understand situated knowledge. In Haiti, we want to give community members access to the latest technology and building techniques. For me, this requires learning the Haitian way of building, and co-creating a shared knowledge base of how we can go out and do housing repair work that pulls from these knowledge bases. One the traditional building techniques here is called clissage, where you weave pieces of wood of varying tensions to create strong foundations and vertical structures. What we’re doing is showing Haitians how they can bolt onto clissage more modern and hurricane-resistant techniques for roof design and installations.