By Sean Burns

Katya Cherukumilli arrived at Cal with a calling. Having spent the first seven years of her life in the southeastern coastal state of Andhra Pradesh, Cherukumilli emphasizes, “The problem of people not being able to meet their most basic needs has always been close to my heart.” During her undergraduate years at Cal (2008-2012) as Regents’ and Chancellors’ Scholar, she majored in Environmental Sciences and minored in Global Poverty & Practice and Energy & Resources. The impacts of climate change were central to her studies and, overtime, water and sanitation challenges in developing regions became the focus of her work.

During her junior and senior year, Cherukumilli sought out a wide range of research opportunities in these fields. She worked at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, researching the impact of climate change on plant species distribution in collaboration with Professor John Harte (ESPM). Under the supervision of Professor Kara Nelson (CEE), Cherukumilli then fulfilled the “practice” component of her minor in Global Poverty through field analysis of the risks associated with water irrigation along the vegetable supply chain in the Indian city of Dharwad, Karnataka. Her concerns were as much with microbes as with social processes—“I asked myself, where is knowledge about how vegetables are irrigated lost from farm to consumption?”

Her undergraduate years culminated with participation in the Haas Scholars program. Selected among one of 20 seniors, Cherukumilli developed her climate change research with Professor Harte into a senior thesis. She describes the interdisciplinary cohort of peers and mentors as “incredible and transformative.” No other setting at Cal had offered her a context where she could expose her ideas, methods, and questions to a group of dedicated people with such a wide range of growing expertise. As she honed her research on ecological responses to climate change, her fellow Haas Scholars worked on issues of immigration law, gender equity, mental health challenges for veterans, and more. The weekly dialogues were rigorous and mind-opening. “You just don’t see this kind of interdepartmental collaboration enough here,” says Cherukumilli.

This point of interdisciplinary collaboration for social progress gets at the heart of what Cherukumilli sees as Berkeley’s greatest educational promise—what many call “the Berkeley difference.” When she made the choice to pursue her doctorate here in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, she knew she had to find pockets at Cal that fostered interdisciplinarity and real-world problem solving. One place she found this intersection was at the Blum Center for Developing Economies. Cherukumilli’s first exposure to the Blum Center was through the Global Poverty & Practice minor. She met her current doctoral advisor, Professor Ashok Gadgil, when he spoke about his work on the Darfur Cook Stove Project for the Blum Center course “Global Poverty: Hopes and Challenges in the New Millennium” (GPP 115).

As a doctoral student in Gadgil’s Lab, Cherukumilli notes that two Blum Center affiliated programs are giving her a chance to amplify the impact of her research. During the spring of 2015, Cherukumilli teamed up with four other Cal graduate students to earn second place in the global health category of the annual Big Ideas@Berkeley competition. Their winning idea emanates from Cherukumilli’s doctoral research; the team is setting out to develop a bauxite-based defluoridation technique for communities whose water source has dangerously high levels of fluoride. The impacts could be massive. According to the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, approximately 200 million people are regularly consuming water with levels of fluoride that dangerously exceed World Health Organization standards (1.5 mg/L (ppm)). Fluoride naturally occurs in many aquifers, but exposure to high fluoride levels can cause detrimental health effects, including anemia and skeletal fluorosis. While de-fluoridation techniques already exist on the market, Cherukumilli’s team aims to significantly reduce the cost and environmental impact of current processes. In July 2015, the project got additional recognition when it earned first place in UC Irvine’s Designing Solutions for Poverty Contest.

Cherukumilli is quick to note that the strength of her defluoridation project resides in the interdisciplinary character of her team. Her partners at Cal include a political science doctoral student and three MBAs—one of whom is also pursuing a public health degree. Cherukumilli notes that Big Ideas created a structured and incentivized forum through which they could apply their shared interests and build upon their diverse skills. While her focus is on technical design, her team members are conducting partnership development, field-testing, marketing, fundraising, and evaluation.

Cherukumilli says she yearns for there to be more curricular and co-curricular spaces at Cal where students—undergraduate and graduate alike—can come together to research and directly engage with pressing social problems. She’s found one such place in the newly launched “designated emphasis” in Development Engineering (Dev Eng) for graduate students. The Dev Eng program, which launched in fall 2014, provides course work, research mentoring, and professional development to students seeking to develop, pilot, and evaluate technological interventions for improving life in low-income settings. Cherukumilli is part of the inaugural cohort of students and faculty forging this emergent discipline. The core course, Dev Eng C200, is taught by Professors Alice Agogino (Mech Eng) and David Levine (Haas Business) and draws students from computer science, public health, city and regional planning, economics, information studies, and more.

For Cherukumilli, the Dev Eng context is ideal because, “confronting these problems from the technical side, I’ve already come to understand how deeply interdisclipinary they are—issues of local context, people, politics, and education. Dev Eng structures a space where this complexity can be explored.”

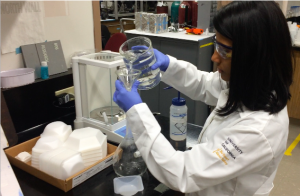

During the summer of 2015, Cherukumilli was busy in the lab, advancing her research on bauxite. In the years ahead, as she completes her Ph.D., she will look to continue her work at a national lab, in a university context, or in the nonprofit sector. Wherever she ends up, it’s clear she’ll carry with her the Berkeley difference—the rigorous analytic capacity to see the complexity of daunting social problems and have the resolve to implement possible solutions.